Matt Rich lives and works in Boston, Massachusetts. He has had solo exhibitions at Project Row Houses in Houston, devening projects + editions in Chicago, the Suburban in Oak Park, IL, VOLTA/NY in New York and Samsøn in Boston, MA. Matt has received fellowships from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Terra Foundation for the Arts and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. His work has been reviewed by Artforum, Art Papers and the Boston Globe.

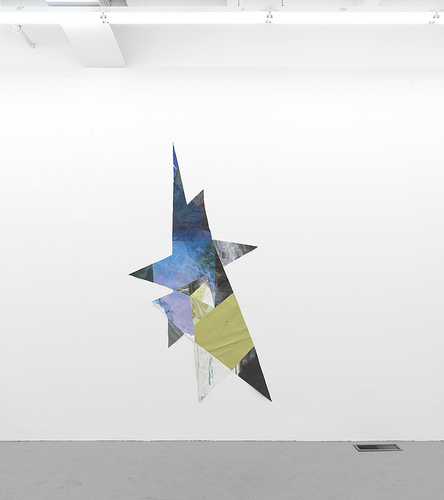

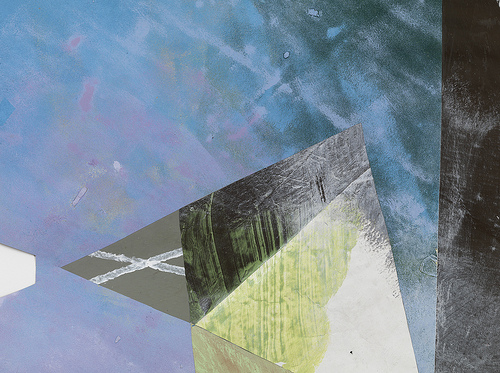

What materials do you use in your work and what is your process like? My cut paper paintings get rid of the canvas and its hired muscle, the stretcher bar. Rolls of 70 lbs drawing paper, coated on two sides with latex and acrylic paint, constitute both image and structure. These sheets of paper are scattered around my studio accruing traces of their movement and use in that space: a kind of studio choreography. The surfaces of my work are built piece-by-piece, the compositions growing and contracting freely without structural restraint. Without a backing structure, individual colors and shapes are open to constant editing or exchange in procedures both deliberate and chance-based (as one example: in process pieces can be flipped to reveal “found” color schemes). My process generates a carefully constructed sense of fragility that is pointed, ultimately, toward an integrated, resolved whole—a whole that articulates this fragility in a sustained and systematic manner.

What kinds of things are influencing your work right now? Emotional play and the significant impact of emotional structures within people, institutions, situations and embedded in interfaces of all kinds is what I find most interesting and powerful in the world. This is why I make the work that I do. While my work has many precedents in visual history, including Richard Tuttle, Ron Davis, Lynda Benglis and Ellsworth Kelly, to name just a few, I have been very influenced by the startling experiential charge in Alison Knowles’ Event Scores from 1961 and Michael Asher’s work, specifically a piece he did at Pomona College in 1970. These works test the audience’s creativity.

How has living in Boston affected your art practice? I grew up in Boston and live and work here now. I moved back here six years ago for a full-time teaching job. I have a studio at one end of my old neighborhood, the South End, and teach on the diagonally opposite end. Frequently, I bisect my old neighborhood, staying current on its comings and goings. There were times in the past that I felt as if I were fourteen years old, walking down the same damn street for the ten thousandth damn time, caught in a time and a place that I thought I had outgrown. Now I thoroughly enjoy these familiar spaces, finding in them an opportunity for a sort of hyper-intimate engagement that encourages attention to smaller and smaller details, allowing already familiar things to resonate more loudly and, in some way, differently.

What are some recent, upcoming or current projects you are working on? Currently I am working on a June solo at Halsey McKay Gallery in East Hampton, NY. Spring of 2013 I will have my second solo exhibition at devening projects + editions in Chicago.

What do you do when you’re not working on art? Teach, mostly. I helped create a class called Interactive Foundations a few years ago. It deals with social-, architectural-, device- and screen-based interactive experience. I was brought in to help build the social and architectural portions but within a semester was teaching the whole class. This was an unexpected and pleasurable challenge, one that has changed my thinking about many things. Basic game theory provided an early structure for describing to my students how everything in this world could be seen as existing within a system, including—our base model for interactivity in the class—ordinary conversation. Takeaways from this experience include: understanding how decisions made in the creation of open-ended systems carry no less specificity than decisions made about closed-systems, and the idea of making something that exists expressly to make something else—making a system in which a viewer/user (viewzer?) is meant to construct their own meaningful experience.

What do you want a viewer to walk away with after seeing your work? The warm glow of relief after effort or a crisis has been averted. An understanding that life will continue as before, but differently.

What are you really excited about right now? Parasites. Favorites include the Sacculina that, upon penetrating her body, makes a female crab care for its clump of larvae as if it were her own “brood pouch” and, after infecting a male crab, compels it to act exactly as the female, including radical physical and behavioral transformations. Also, the lancet fluke that gets ingested by a snail only to disagree with its digestive system and get puked out in a slimy substance that is particularly attractive to ants. After being ingested by a passing ant it compels the ant to walk to a high place at dusk—which is precisely when large mammals enjoy feeding on tall blades of grass. Once the blade of grass bearing the ant that is infected by the parasite is ingested, the parasite settles in the home that it desired from the beginning.

These stories are thrilling and unbelievable and yet seem totally inevitable. These processes are so loose as to appear random but bear the marks of a perfect, tested system. Like many people, I learned of the wonderful, complex world of parasites on one of the variations of a program put out by Radiolab on the topic and immediately ran out to purchase Parasite Rex by Carl Zimmer, a guest on the Radiolab program, which is the brilliant source for the stories retold above.

What were you like in high school? Goofy and fast. A mama’s boy. A hard but inefficient worker.

*All photos credit: Clements Photography & Design