Tell us a little bit about yourself and what you do.

I am an artist, art enthusiast, and occasionally a curator when time, space, and resources align. I’m also a brother, son, uncle, friend, xyz. Art is all consuming, and a majority of my time is spent creating work and traveling to see and experience art in various contexts. I also listen to a lot of different kinds of music. My annually accrued listening hours on Spotify are through the roof. For the past three years, I’ve been serving as the community co-chair for Artist Trust’s annual art auction and fundraiser, helping to support the organization’s mission of empowering and providing resources for artists in Washington State. I currently sit on the board of the Lillian Miller Foundation, which is dedicated to advancing educational opportunities for LGBTQ+ youth in the arts and culinary fields, as well as On The Boards, an organization that produces unique performance projects by leading artists around the world and brings forward-thinking performance to Seattle. Additionally, I’ve been proudly serving as a committee member for the Betty Bowen Award, which honors a Northwest artist each year with an unrestricted cash prize and an exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum. I thrive on staying active and engaged, embracing the pressure of fulfilling commitments, and finding joy in both entertainment and adventure.

You work extensively with polylactic acid (PLA), a material typically used for 3D printing. How were you introduced to the medium, and what do you appreciate about working with it? How do you think using plastic as a medium affects the conversation around consumerism fostered in your work?

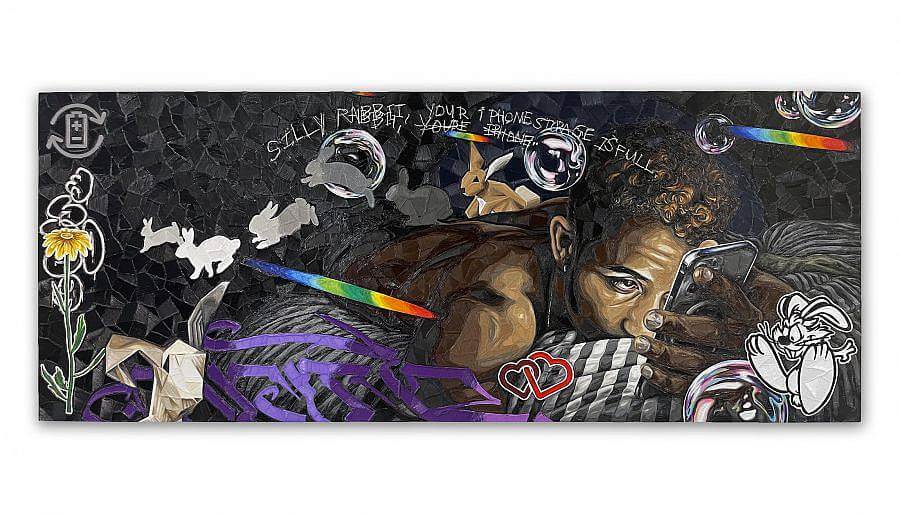

I first encountered polylactic acid (PLA) while I was a student at Cornish College of the Arts. I was primarily working in sculpture at the time, spending most of the day in the fabrication lab. The department would often get new toys and tools, and I remember the day the lab introduced their first 3D printer. I was captivated by the mechanics of the machine and the coding and software behind it. It merged many of my interests at the time, and I became intrigued by the idea of subverting the concept of “machine-made” by replicating its process through my own hand. At the time, I wasn’t interested in traditional painting or using brushes. Experimenting with the PLA felt reminiscent of my days tattooing. The process of applying the PLA and controlling the device to create line and fill is very similar to the way you’d hold a tattoo machine. The whole thing felt very natural and nostalgic.

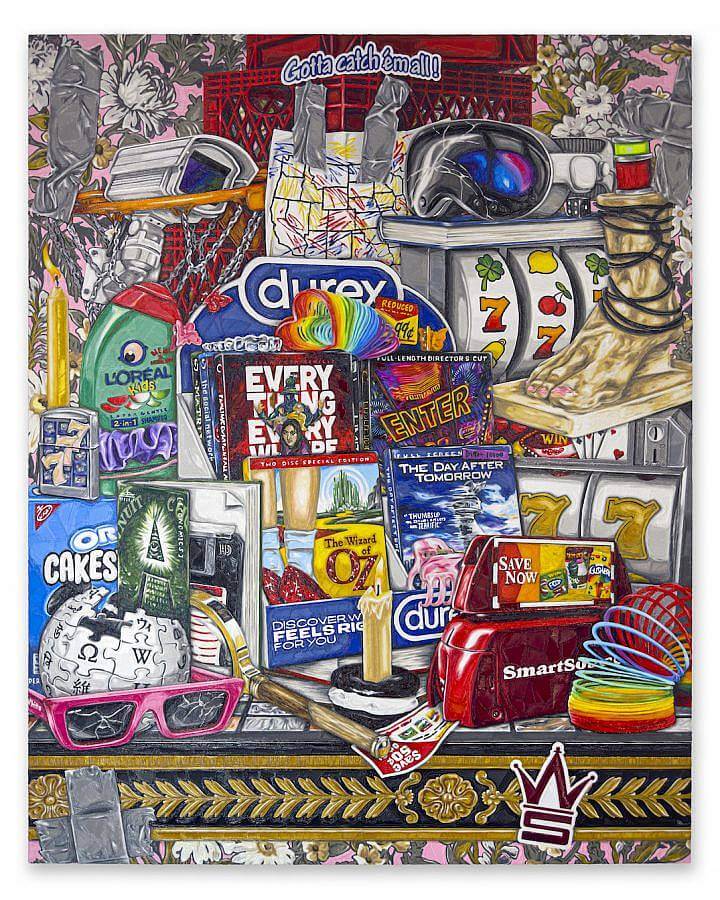

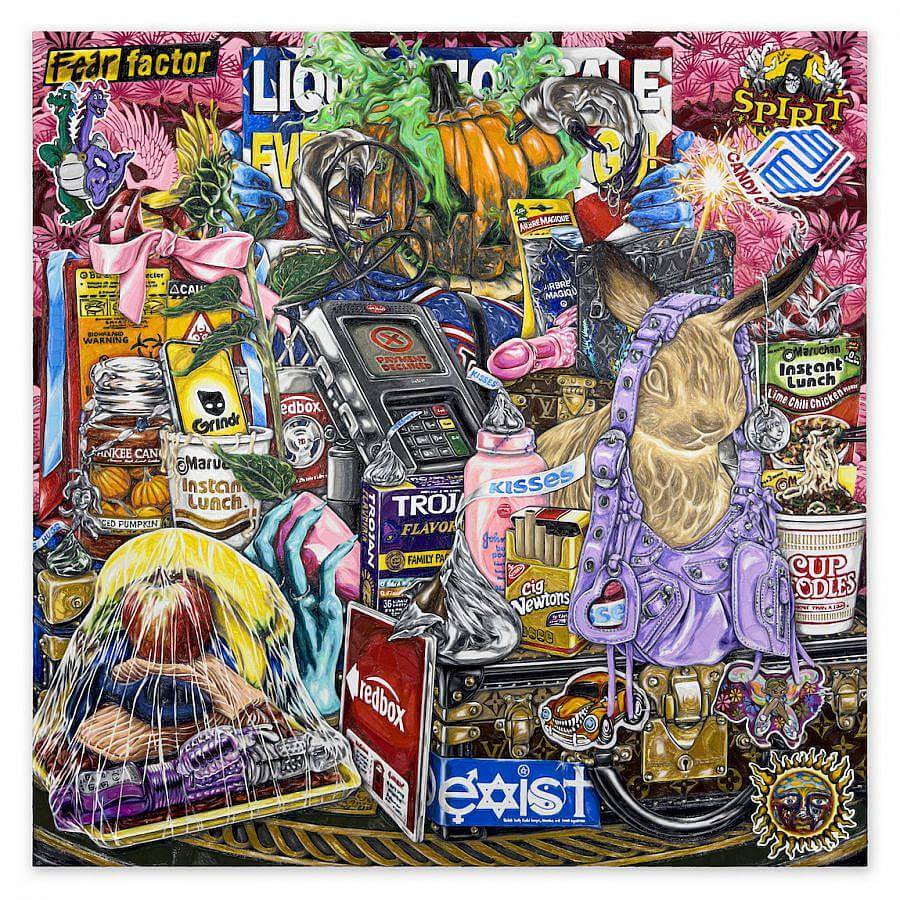

What I appreciate most about PLA is its deceptive nature; it often presents as an unfamiliar material, inviting curiosity. It also maintains a complexity that continues to challenge me, even after years of working with it. My choice to use the PLA is rooted in a desire to create a direct connection between content and concept—many of the objects I depict are made from the same material as their real-world counterparts. The synthetic, artificial quality of PLA speaks to broader themes in my work, including the nature of consumerism, capitalism, and the media-driven world we live in.

Is there a moment you look back on as being formative to your identity as an artist?

A defining moment was my time in New York City during my third year at Cornish College of the Arts. I participated in the New York Studio Residency Program, an exchange with the School of Visual Arts, which has since been discontinued. Spending an entire semester immersed in the city was transformative. I realized then that I wanted to pursue art as a serious career. Working closely with mentors like Adam Parker Smith and Bill Powhida and learning from critics like Jan Avgikos deepened my understanding of the art world. The program was phenomenal. As a group, we were privileged with studio visits and exhibition walk-throughs led by artists such as Nicole Eisenman and Baseera Khan, and visiting artist lectures from figures like Mark Leckey added layers of insight that profoundly shaped my practice and understanding of the art-world.

My interest in art stretches back as far as I can remember, though it took time to embrace the title of “artist” publicly. Before I was able to drive I was really into drawing, painting and tattooing; creating still and sometimes permanent images became a form of escapism for me. Later, I became fascinated by time-based media and studied film theory and production in California, thinking that would become my path. The years I spent tattooing were particularly formative, teaching me to convey ideas through imagery, while my time studying film refined my skills in composition and narrative storytelling.

Describe your current studio or workspace.

I’ve had a few studios over the years. But for the past four years, I’ve been working out of an intimate studio building that is very close to my apartment, which was a major factor in choosing it, and has proved to be a huge benefit. It’s modest—large enough to display a few completed works, keep some pieces in progress, and a little space for reading, writing, and just chillin’ out. The rent is reasonable, and one of my favorite aspects is the ability to play music as loud as I like.

While the space has worked for many years, it does set a limit on how large I can go. I envision building a more spacious studio someday—one that would allow me to create even larger works and, ideally, have the option to stay overnight.

Do you have any rituals when you arrive at your studio/workspace?

First things first; lights, morning news, and emails. A grounding routine that helps me ease into the space; transition from the outside into the focused and unbothered atmosphere of my sanctuary.

What is your experience working in Seattle, away from coastal art hubs like New York or LA? Are there any limitations or benefits?

Seattle has become my home over the past decade, and while I regularly travel to New York and LA to see art and visit family, the city has its own distinct character. Seattle isn’t widely recognized as an art hub, but it does hold a rich history of nurturing great artists. The city has become even less of an art destination city considering the death of Paul Allen, and the rising living costs here, but I am optimistic about its potential to grow. The Pacific Northwest is home to a few excellent museums and curators, and like many places, it struggles with the infrastructure necessary to keep artists present and working. That in itself could be the subject of a much larger conversation.

One of the main challenges I’ve encountered is the high cost of shipping, given Seattle’s distance from major art centers like New York, London, Paris, and Berlin. However, the city’s advantages lie in its strong sense of community and support for emerging artists. Seattle is a place where younger artists can find opportunities and a network that encourages growth.

Does an artist’s geographic location matter given social media’s ability to reach globally?

To some extent, an artist’s location is less critical if they actively engage with social media. The reach and power of social media are unparalleled, providing artists with a platform to connect with audiences globally. However, artists are naturally drawn to places that inspire and refresh them, which often leads to a kind of migration and movement that goes beyond the digital space. Geographic location still holds certain advantages. Galleries, museums, and institutions often prefer engaging with artists in-person, conducting studio visits and sometimes fostering connections locally. Proximity to where “art is happening” is important as those regions and hubs can provide opportunities that aren’t always feasible across long distances, especially when budgets are limited. A good example of this regional focus is seen in one of my favorite recurring exhibitions, Made in L.A., which highlights the value of geographic ties in the art world.

Are there any influences that are core to your work?

Cable TV, the internet of course (growing up with and without it) and my adolescence in the rural Southwest remain significant influences to my overall artistic practice. In terms of artistic inspiration, I am incredibly influenced by 17th-century Dutch still life paintings. I draw from the narrative and compositional intricacies in those works by artists like Vermeer, Caravaggio, Van Beyeren. The intricate engravings and carvings of printmakers like Hendrick Goltzius also captivate me—their mastery over mark-making through a subtractive process is mesmerizing and seductive, even though it contrasts with my approach. Additionally, I am inspired by contemporary artists like Lauren Halsey, Jordan Wolfson, Henry Gunderson, Paul McCarthy, and Kerry James Marshall, who continue to inform my practice.

Though your work is highly reflective of the 21st century in terms of both the medium you use and the compositions you craft, your inclusion of status symbols and subcultural signifiers in your still life works speaks to a longstanding art history. Was there a formative art historical period for your practice?

It’s often in the small, overlooked details of everyday life that we find the underpinnings of larger systems. When we begin to notice those hidden fragments, it opens up space for more expansive and nuanced conversations that deviate from mainstream narratives. Questions emerge about why things function as they do, which elements are fundamentally essential, and how symbols, iconography, and even hieroglyphics have evolved into the instantly recognizable imagery of today. This process of unraveling reveals how these threads, woven together over time, have shaped human experience.

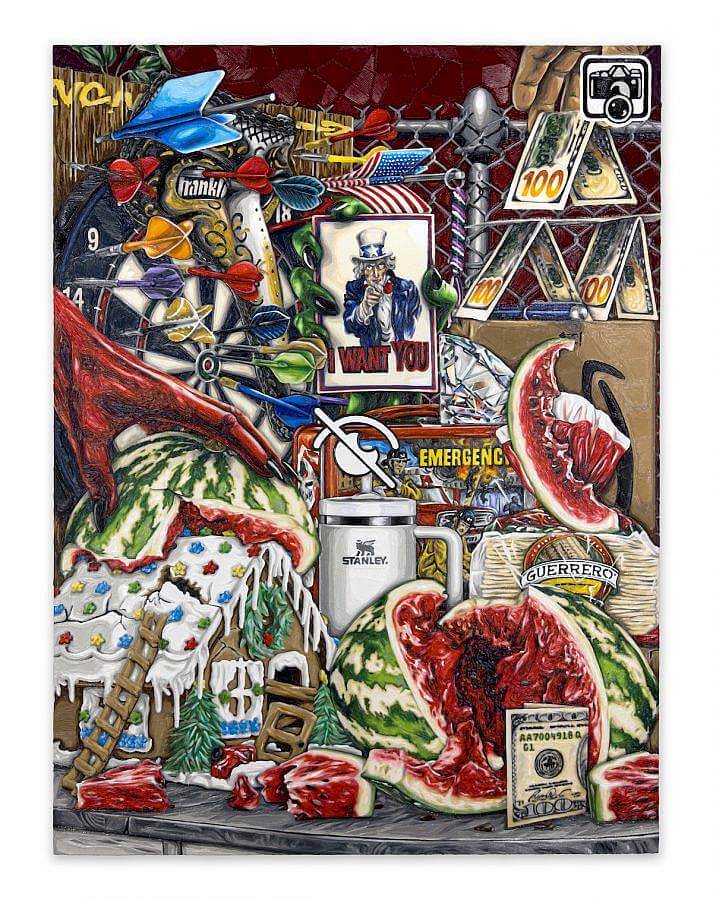

Conceptually, 17th-century Dutch Vanitas painting has been especially formative for me. The tradition’s way of embedding layered meaning in still lifes has deeply influenced my own storytelling approach. I like to think of my practice as an extension of that legacy, but updated with contemporary tools, materials, and perspectives. I create work that I would like to see in the world—paintings that invite viewers into challenging questions through an accessible entry point. As the layers of my work are peeled back, the metaphors become more complex, inviting deeper contemplation while retaining the approachable surface that encourages different audiences to engage.

The imagery referenced in your still life works is familiar and accessible to a wide audience, particularly those who were born into Gen Z or those who are chronically online. What are you looking for when you source your reference material and what kind of conversation do you hope it fosters for the viewer? Has the imagery you reference evolved as your practice has developed?

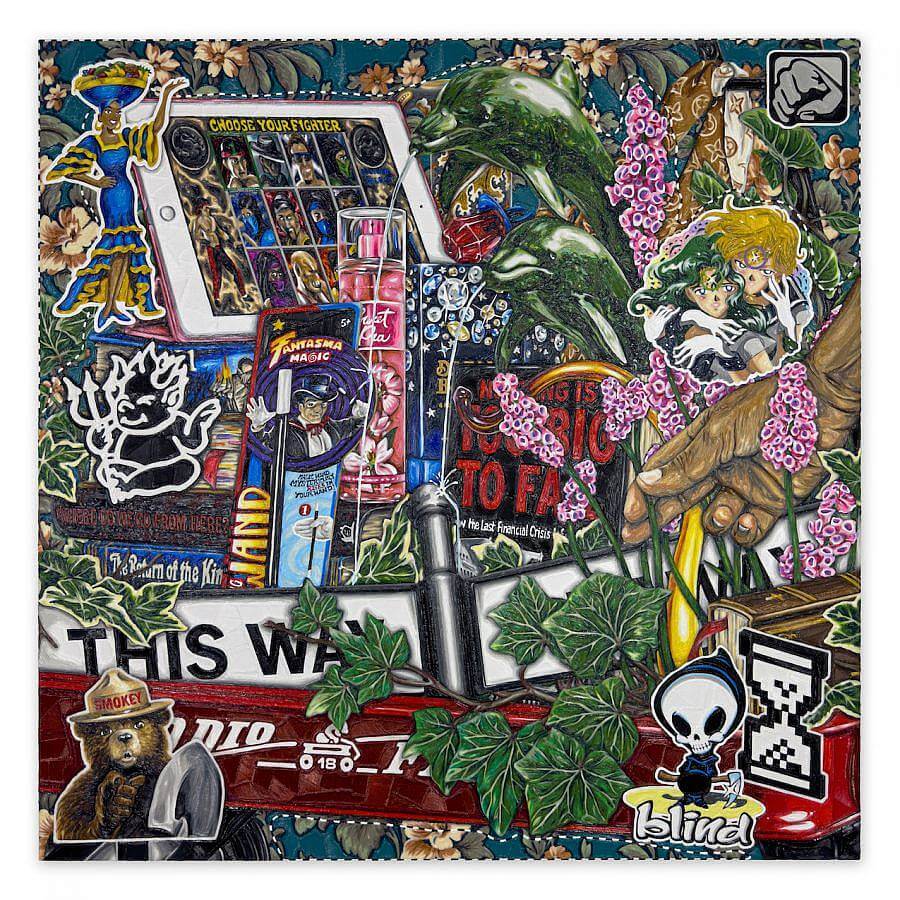

I typically source material that is deeply familiar to me—whether it’s technological artifacts or cultural references from my childhood, or broader cultural phenomena that resonate with the present moment. This often includes both outdated and obsolete technology as well as new social platforms and memes that capture the essence of the cultural zeitgeist. Once I identify metaphors and symbols that encapsulate a specific moment or cultural movement, I begin layering additional objects and imagery that are peripheral or adjacent to those core ideas. This helps to build a more intricate and nuanced narrative.

Many of my works evolve into webs or clouds of interconnected information, beginning with a central concept that gradually expands outward. The layers invite viewers to engage with different elements based on their own associations and experiences, making the work accessible to those familiar with the references. When I first engaged with the tradition of 17th-century vanitas paintings, I noticed a similar strategy in how they conveyed layered meanings through symbols and objects. That realization has influenced how I approach creating complex visual narratives in my work and practice.

You’ll be showing a new body of work in New York this month, as part of the Greg Kucera Gallery’s participation in the Art Dealers Association of America’s annual art fair. How does this work build on what you’ve accomplished in your practice so far?

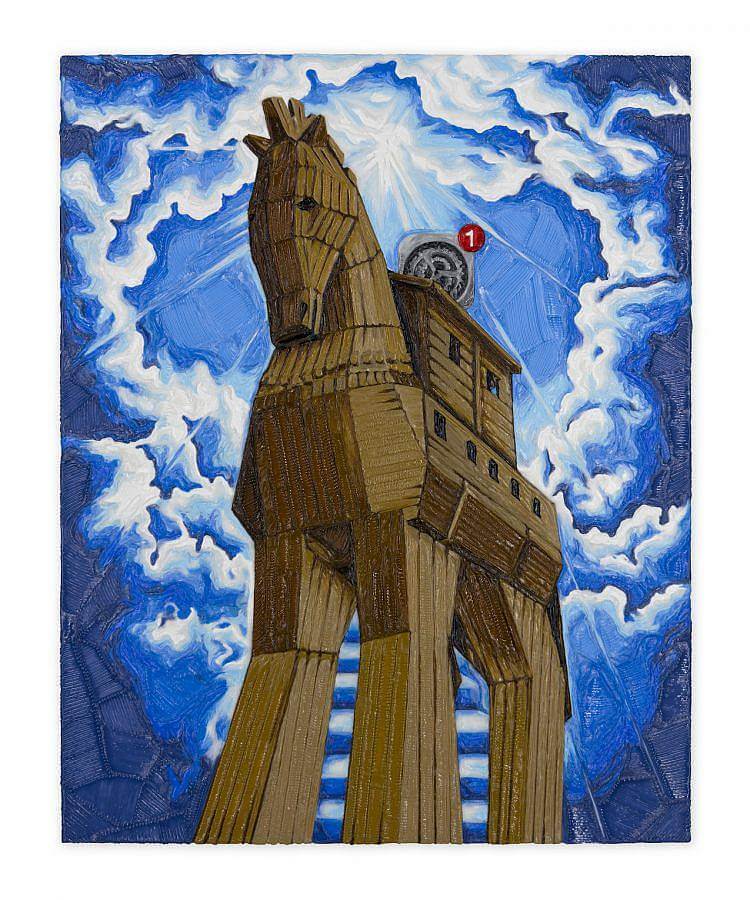

For this upcoming fair, I’ve taken the opportunity to explore a few new directions in my practice—ideas I’ve been hesitant to fully embrace until now. These new works represent subtle pivots, condensed ideas that unfold more powerfully in the right format or space, and at their core, this body of work is steeped in themes of magic, performance, and sorcery, while still rooted in the familiar tropes and symbols that define my practice.

One thread of my ongoing research has been centered on persona, identity, and the ways we construct and represent ourselves. In one particular piece, I wanted to address that discourse from the very beginning—before we choose how to curate our narratives. It’s about the moment of decision: What will one say? How will one choose to present themselves to the world? The work takes on a trophy-like quality but is also intentionally bare, like a mannequin, inviting the viewer to figuratively “make up” their own narrative. It asks how we display ourselves to the world each day, and what those choices mean.

Another work draws direct inspiration from Goya’s Three Witches, paralleling the current state of global anxiety surrounding AI and its apocalyptic associations. It’s a depiction of an age-old narrative: hearing the warning calls and either choosing to intervene or to willfully ignore them, a classic tale made more urgent by contemporary fears.

What is one of the bigger challenges you and/or other artists are struggling with these days and how do you see it developing?

A significant challenge for most artists is the struggle to sustain themselves solely through their creative work. Finding a solution to this issue is complex, and I don’t have anything close to a definitive answer. However, in Seattle, there’s a non-profit organization called Artist Trust that I deeply believe in and support. It serves as a crucial resource for artists, offering career guidance, workshops, and tools for professional development. More importantly, it is one of Washington State’s largest direct grantors, providing artists with financial support that goes straight into their pockets. While these resources can’t support every artist in the region, they have the power to transform lives and sustain artistic practices.

There are other resources out there like Artist Trust, and I encourage all artists to get familiar with those in their regions. Without this kind of support, artists may be compelled to relocate, which erodes the creative and cultural fabric of a place. When artists leave, so does the art; when art diminishes, culture fades, and with it, the unique essence that defines a community. This cycle is self-perpetuating and leads to lasting, potentially irreversible consequences for creative landscapes.

Do you have a dream project?

I appreciate this question because it serves as a source of motivation. I have always wanted to do something with billboards, and exploring relief and carving techniques on cement is also interesting—perhaps along concrete walls lining freeways. Murals intrigue me as well, but I’m particularly drawn to the idea of using a subtractive process to craft permanent images. This approach feels connected to the earliest forms of artistic expression, like cave carvings and stone inscriptions. While I haven’t yet ventured into the public arts sector, I would be interested in the possibility of translating one of my “paintings” into a freestanding sculpture. My aim would be to ensure that the conceptual depth and development align with the same intent and rigor I bring to my studio practice.

Interviewed by Luca Lotruglio.